The Kosi, is a transboundary river between Nepal and India and is one of the tributaries of the Ganges that flows through the plains of the northern Indian state of Bihar. The Kosi is notorious for its devastating floods, which causes extreme damage to lives and livelihoods (flood related deaths in India account for a fifth of global flooding deaths).

The Kosi, is a transboundary river between Nepal and India and is one of the tributaries of the Ganges that flows through the plains of the northern Indian state of Bihar. The Kosi is notorious for its devastating floods, which causes extreme damage to lives and livelihoods (flood related deaths in India account for a fifth of global flooding deaths).Kosi embankments were built nearly five decades ago to confine the river and provide security from flooding. But despite this, breaches have occurred consistently and have left vast Kosi dependant regions in North Bihar, waterlogged. In 2008, the flood affected over 3 million people and the hardest hit were communities in 380 villages trapped between the two embankments of the river.

The Voice of the Kosi expedition was conceived to give marginalised groups along the Kosi river an active voice in their own equitable and sustainable development. The overall purpose was to contribute towards the sustainable and equitable development of river basins worldwide.

Geographical Background

The Kosi is a transboundary river between Nepal and India and is one of the tributaries of the Ganges that flows through the plains of the northern Indian state of Bihar.

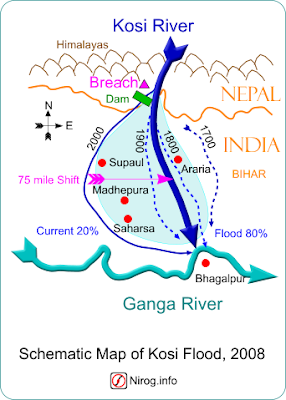

The river, along with its tributaries, drains a total area of 69,300 km2 (26,800 sq mi) up to its confluence with the Ganges in India (29,400 km2/11,400 sq mi in China, 30,700 km2/11,900 sq mi in Nepal and 9,200 km2/3,600 sq mi in India). The watershed also includes part of Tibet, such as the Mount Everest region, and the eastern third of Nepal.

The Kosi river flows north to south, from Himalayas in Nepal & Tibet to Ganges in Bihar state of India. Usually due to heavy silt deposition, the river keeps taking longer curved paths to drain into the Ganges. Due to this, the river has shifted its course in the last 300 years. It is believed to have shifted its course over 120 kilometres (75 mi) from east to west.

Historical background of Kosi embankments

The Kosi has been part of folklore and legends in the basin area for several centuries. As explained in the above section, the river has historically been prone to floods. After India got its independence from the British in 1947, it drew up an agreement with Nepal to build the embankments in 1955. The idea behind this was to free millions of people from the devastation that was caused by the floods every year. According to the agreement, the responsibility of maintaining these embankments was vested in the Government of Bihar.

The embankments instead of protecting people ended up creating a bigger and much worse problem of trapping millions of people within it. This includes 386 villages spread across the four districts of Bihar (Saharsa, Supaul, Madhubani and Darbhanga) and 13 blocks (smaller administrative units – namely Basantpur, Kishanpur, Supaul, Nirmali (including Bhaptiahi), Nauhatta, Mahishi, Simri Bakhtiyarpur, Salkhua, Laukahi, Marauna, Ghoghardiha, Madhepur and Kiratpur)

The embankments instead of protecting people ended up creating a bigger and much worse problem of trapping millions of people within it. This includes 386 villages spread across the four districts of Bihar (Saharsa, Supaul, Madhubani and Darbhanga) and 13 blocks (smaller administrative units – namely Basantpur, Kishanpur, Supaul, Nirmali (including Bhaptiahi), Nauhatta, Mahishi, Simri Bakhtiyarpur, Salkhua, Laukahi, Marauna, Ghoghardiha, Madhepur and Kiratpur)Before the villagers understood the gravity of the situation and were able to raise the alarm and demand rehabilitation, it was already 1956 and 50kms of construction of the embankments had been completed. The Government for its part assured the ‘trapped’ people that the embankments, when completed, would cause only a marginal rise of four inches in the water level within them and that they had nothing to worry about. The people, however, maintained that the land around the Kosi sloped westwards and that any increase in the water level would spell doom for those trapped within the embankments.

At a meeting of the Kosi Control Board in Patna in 1956 members of the Central Water Commission opposed any move to resettle people displaced by construction of the embankments, on the plea that it would set a bad precedent and that people would begin demanding rehabilitation in all such projects. Good sense however prevailed and the rehabilitation issue remained alive. In 1956, the floods in the Kosi devastated those living within the embankments. Outside the embankments, the villages suffered water-logging from the stagnant water that could not make its way to the river because of the embankments.

A movement to rehabilitate villagers trapped within the Kosi embankments gained momentum in 1957. As resistance grew, the government prepared a rehabilitation package, but it later realised that it was severely under-budgeted and shelved the plan. As pressure mounted, the Government then announced a proportionate package of rehabilitation. The state announced in 1958, that the government would provide land to victims in flood-protected areas close to the embankments; that the government would arrange land for schools and roads; that rehabilitation sites would be provided with tanks, wells and tube wells for water supplied by the government; that house-building grants would be made available to the affected people; and that the government would ensure easy access to farmers’ fields by providing an adequate number of boats.

A movement to rehabilitate villagers trapped within the Kosi embankments gained momentum in 1957. As resistance grew, the government prepared a rehabilitation package, but it later realised that it was severely under-budgeted and shelved the plan. As pressure mounted, the Government then announced a proportionate package of rehabilitation. The state announced in 1958, that the government would provide land to victims in flood-protected areas close to the embankments; that the government would arrange land for schools and roads; that rehabilitation sites would be provided with tanks, wells and tube wells for water supplied by the government; that house-building grants would be made available to the affected people; and that the government would ensure easy access to farmers’ fields by providing an adequate number of boats.By 1960, only 70 villages were resettled. This meant that another nine years would be needed to ensure rehabilitation for all the embankment victims. By 1972-73, only 32,540 families out of a total of around 45,000 families were given their first grants to construct houses; 10,580 families were given second installments; none received the third and final installment. This arrangement did not work since the rehabilitation sites were slowly becoming waterlogged and people began to return to their old villages. The government interpreted this as a move by people to return to their ancestral property and so the rehabilitation process ended before it was even completed.

The state believed that not all the land within the Kosi embankments would be ruined as a result of the embankments, and that agriculture would continue to be practiced there. It was against this background that the government appointed a committee, in 1962, to look into the problems of agriculture, health, industry, revenue collection, extension of securities and cooperation. The state development commissioner, land reforms commissioner and chief administrator of the Kosi project were all members of this committee. But the committee did not perform.

Then, in 1967, another committee was constituted under the chairmanship of the Kosi area development commissioner whose job it was to suggest programmes for victims of the project, in the agriculture, cooperation, industrial development and economic rehabilitation sectors. This committee too was non-functional. In 1981, another committee was constituted to look into the problem of economic rehabilitation of the embankment victims. This committee gave its report in 1982; in 1987 the government accepted its recommendations.

Then, in 1967, another committee was constituted under the chairmanship of the Kosi area development commissioner whose job it was to suggest programmes for victims of the project, in the agriculture, cooperation, industrial development and economic rehabilitation sectors. This committee too was non-functional. In 1981, another committee was constituted to look into the problem of economic rehabilitation of the embankment victims. This committee gave its report in 1982; in 1987 the government accepted its recommendations.Based on the recommendations of this Committee, the state government constituted the Kosi Pirit Vikas Pradhikar (Kosi Sufferers Development Authority) the same year. While recommending the constitution of the Authority, the then chief minister of Bihar, asserted that there was probably no other place in the country where so many people were exposed to the fury of river flooding. The people had lost all hope of a better life, and his “determined government” was committed to their overall development.

However, since its inception in 1987, the Kosi Sufferers Development Authority has remained a defunct body. It has no building or office of its own; it has no vehicles; and ‘deputation employees’ man it. It does not even have a budget.

The situation today

Education

There are few primary schools within the embankments and the schools which do exist are of very low infrastructural quality (eg: school buildings do not have roofs.) As a result very few students and teachers are enrolled here

Health

Doctors and health department personnel generally do not visit the health centres in the area and during the rainy season, they cannot do so even if they wanted to because of the river’s heavy currents and cutting off of all means of access to these villages

Infrastructure

There is no electricity, no permanent roads, no colleges, no hospitals, no cinemas, no banks and no government offices in the embankment villages.

Employment

Even though there is a provision for reservation of 15% of jobs in the districts for the victims of the Kosi embankments, so far, no one has benefited from this scheme – not even for positions in the Kosi Sufferers Development Authority.

Social stigma

The people living within the embankments avoid marriages as there are no employment opportunities and therefore is no scope to feed families. The communities are slowly being forgotten since even the politicians do not pursue their issues at the appropriate forums.

A typical house, a typical school and a typical village.....

WITHIN THE KOSI EMBANKMENTS

No comments:

Post a Comment