Here is a film about what the Kosi scouts saw and did and how they developed a youth manifesto.

24 April 2009

The Youth Manifesto

Based on all the information collected by the scouts, they developed a youth manifesto on each of the nine stops. They then decided to put all of this together and create a summary of all the issues. They did this by answering these basic questions:

• What conclusions do youth make from this? (from the information exchange)

• What would youth like others (adults or politicians) to be told? What would they not like told?

• What are the common things, issues and actions youth along the Kosi share? What’s different?

The scouts discussed this amongst themselves, with the Praxis team and verified the information with the larger community (as in the photos below)

Presented below is a summary of issues for developing a Youth Manifesto for the Kosi

Benefits from the River

Losses due to the River

Solutions suggested by the youth

Draft Policy Issues

• What conclusions do youth make from this? (from the information exchange)

• What would youth like others (adults or politicians) to be told? What would they not like told?

• What are the common things, issues and actions youth along the Kosi share? What’s different?

The scouts discussed this amongst themselves, with the Praxis team and verified the information with the larger community (as in the photos below)

Presented below is a summary of issues for developing a Youth Manifesto for the Kosi

Benefits from the River

- Fodder is available from 3-4 months to 6-7 months in a year

- Rice and wheat cultivation is good.

- The period of 7 to 8 months prior to the flood is gainful.

- There are protective embankments here.

- Tube wells can be dug easily (upto 25 to 30 feet) function well and water is available throughout the year

- During the flood, irrigation becomes easy.

- The land is never infertile due to the proximity of the river.

Losses due to the River

- During floods, both embankments are inundated.

- Some villages are prone to water logging.

- For three months after the flood much devastation has to be faced and survival during the 3 to 4 months of flood (June to August) is quite difficult

- It is also difficult to maintain livestock during this period due to unavailability of fodder.

- Wild animals cause harm to the people, especially children.

- During the flood most people are forced to leave their homes and escape elsewhere.

- Drinking water gets contaminated with iron deposits for several days after the flood.

- It is difficult to access market places.

- Floods lead to destruction of crops (The wheat crop is destroyed every year)

- There are sand deposits in the field, which render them uncultivable.

- Lives are lost due to the flood.

- Sanitation facilities are poor during the flood causing difficulty especially to the women.

- A number of diseases break out in the village during the flood such as malaria, diarrhoea, etc.

- Loss of property takes place due to floods.

- Fields are destroyed due to the floods.

- Floods lead to scarcity of food.

- Medical facilities during floods are inadequate.

- There are no transport facilities.

- The school building gets flooded leading to difficulty in holding classes.

Solutions suggested by the youth

- It is essential to construct guide embankments to prevent floods.

- Sand deposits from the floor of the river need to be removed.

- Boats need to be made available in adequate numbers for evacuation during floods.

- Assistance from the government should come before the flood.

- There should be a community building (for shelter during the flood).

- A guide embankment should be built. Strong security embankments should be built so that the flood waters do not reach the homes of the villagers.

- Trees should be planted on the dam/embankment. Due to flooding, the roads give away. So there should be trees planted along the roads.

- The flow of the river should be divided into multiple streams.

- The youth should unite and assume leadership of any such endeavours by forming youth federations or associations. There are no Youth Associations in the village that can work during calamities or negotiate with the Government during floods to claim their rights and put forth their demands

- There should be a health centre and health care facilities (It is essential to have at least one health centre in the village or at least in the Panchayat)

- Compensation should be provided for lost land.

- There should be arrangements for fodder.

- There should be arrangements for boats.

- There should be arrangements for drinking water.

- The water should be allowed to flow out.

Draft Policy Issues

- The first step should be to exempt submerged land from tax and then to construct a strong security embankment.

- Direct the flow of the river properly (sand deposits on the bed of the Ganga need to be removed)

- Availability of fodder to be extended from the current 3 to 4 months to throughout the year.

- Devastation due to flood that stretches over 3 months should be somehow reduced to a maximum of 15 days.

- Destruction of fields should be prevented and crops lost to floods should be protected.

- Medical facilities should be easily available to people.

- There should be primary schools in all the villages.

- Villagers who lose their land to the flood should be compensated by the government.

- Safe drinking water should be available to the people of the villages.

- The youth should unite and assume leadership of any such endeavours.

Peepar Ratti

After having visited eight communities, the scouts had a fairly good idea of what issues were faced by communities that lived along and depended on the river. Their next stop was Peepar Ratti where they spoke to the youth as well as adults in the larger community.

After having visited eight communities, the scouts had a fairly good idea of what issues were faced by communities that lived along and depended on the river. Their next stop was Peepar Ratti where they spoke to the youth as well as adults in the larger community.Panchayat: Nauhatta East

Population: 1500

Children attending school: 200

Anganwadi: 1

Major Occupation : Cultivation

Barhara

At Barhara village, the scouts found out this information:

Village: Barhara

Panchayat: Marauna

Population: 60 households

Number of children Children: 1000

Anganwadi: 2

School: High school

Major Occupation: Cultivation

They spoke to Anjani Kumar, 20, who said that besides the fact that Barhara village is trapped between the Kosi embankments, it faces an acute problem of lack of connectivity and transport facilities. To start with, there are very few hospitals in the entire district and to get from the village to the closest functional hospital, the residents have to travel either by foot or ride a motorcycle (which most people cannot afford). As a result, the villagers have no choice but to rely on untrained private practitioners for non-sever health issues. In case of serious ailments, when patients cannot be taken on motorcycle, residents shoulder their cots and carry them to the hospital at Nirmalli, several miles away. This is the situation during most times of the year.

They spoke to Anjani Kumar, 20, who said that besides the fact that Barhara village is trapped between the Kosi embankments, it faces an acute problem of lack of connectivity and transport facilities. To start with, there are very few hospitals in the entire district and to get from the village to the closest functional hospital, the residents have to travel either by foot or ride a motorcycle (which most people cannot afford). As a result, the villagers have no choice but to rely on untrained private practitioners for non-sever health issues. In case of serious ailments, when patients cannot be taken on motorcycle, residents shoulder their cots and carry them to the hospital at Nirmalli, several miles away. This is the situation during most times of the year.

When the river floods and there are outbreaks of water related illnesses like diarrhoea and malaria, Archana Gupta (one of the residents) mentioned that there are a minimum of ten deaths a year, mainly among infants – all because there are inadequate health facilities.

The lack of access to these basic facilities frustrates Anjani and other youth, but what makes the problem worse is that there are no education or employment facilities either and no channel for the youth to engage their energy productively. As a result most young men resort to alcohol. According to Anjani, children as young as fifteen years of age are now getting addicted. Due to their drunken and unruly behaviour, this has also become a security concern for many.

The lack of access to these basic facilities frustrates Anjani and other youth, but what makes the problem worse is that there are no education or employment facilities either and no channel for the youth to engage their energy productively. As a result most young men resort to alcohol. According to Anjani, children as young as fifteen years of age are now getting addicted. Due to their drunken and unruly behaviour, this has also become a security concern for many.

When asked what steps the youth could take to improve the living condition in Barhara, Anjani emphasises on the need to break out of conventional modes of thought and adopt a progressive mindset. The village he says is like a frog caught in a well. The metaphor seems more than appropriate what with the more than acute transport and communication problem that the village is faced with.

Thus despite having marginally better infrastructure than its neighbours, the youth of Barhara are forced to demand amenities as basic as roads, public transport, employment opportunities and quality education and healthcare.

Village: Barhara

Panchayat: Marauna

Population: 60 households

Number of children Children: 1000

Anganwadi: 2

School: High school

Major Occupation: Cultivation

They spoke to Anjani Kumar, 20, who said that besides the fact that Barhara village is trapped between the Kosi embankments, it faces an acute problem of lack of connectivity and transport facilities. To start with, there are very few hospitals in the entire district and to get from the village to the closest functional hospital, the residents have to travel either by foot or ride a motorcycle (which most people cannot afford). As a result, the villagers have no choice but to rely on untrained private practitioners for non-sever health issues. In case of serious ailments, when patients cannot be taken on motorcycle, residents shoulder their cots and carry them to the hospital at Nirmalli, several miles away. This is the situation during most times of the year.

They spoke to Anjani Kumar, 20, who said that besides the fact that Barhara village is trapped between the Kosi embankments, it faces an acute problem of lack of connectivity and transport facilities. To start with, there are very few hospitals in the entire district and to get from the village to the closest functional hospital, the residents have to travel either by foot or ride a motorcycle (which most people cannot afford). As a result, the villagers have no choice but to rely on untrained private practitioners for non-sever health issues. In case of serious ailments, when patients cannot be taken on motorcycle, residents shoulder their cots and carry them to the hospital at Nirmalli, several miles away. This is the situation during most times of the year.When the river floods and there are outbreaks of water related illnesses like diarrhoea and malaria, Archana Gupta (one of the residents) mentioned that there are a minimum of ten deaths a year, mainly among infants – all because there are inadequate health facilities.

The lack of access to these basic facilities frustrates Anjani and other youth, but what makes the problem worse is that there are no education or employment facilities either and no channel for the youth to engage their energy productively. As a result most young men resort to alcohol. According to Anjani, children as young as fifteen years of age are now getting addicted. Due to their drunken and unruly behaviour, this has also become a security concern for many.

The lack of access to these basic facilities frustrates Anjani and other youth, but what makes the problem worse is that there are no education or employment facilities either and no channel for the youth to engage their energy productively. As a result most young men resort to alcohol. According to Anjani, children as young as fifteen years of age are now getting addicted. Due to their drunken and unruly behaviour, this has also become a security concern for many.When asked what steps the youth could take to improve the living condition in Barhara, Anjani emphasises on the need to break out of conventional modes of thought and adopt a progressive mindset. The village he says is like a frog caught in a well. The metaphor seems more than appropriate what with the more than acute transport and communication problem that the village is faced with.

Thus despite having marginally better infrastructure than its neighbours, the youth of Barhara are forced to demand amenities as basic as roads, public transport, employment opportunities and quality education and healthcare.

Rholi

Rholi was the next stop.

Panchayat : Rholi;

Population : 1000, Anganwadi: 1;

School: Primary and Middle School; Children attending school: 300; Major Occupation: Labour

____________________________________________________

An interesting youth that the scouts met was twenty five year old Prakash Mani who is a resident of this flood-affected village which has a population of 1000. The entire district (Supaul) has only 52 high schools for a population of over five lakh (five hundred thousand) children aged between five and fourteen years. This means that for every ten thousand children passing out of middle school, assuming that they all reach middle school in the first place, there is only one high school. Prakash’s village is one of the exclusive few to have a middle school.

However, the quality of education at this middle school is quite poor, since there are no competent teachers. To top this of, is the fact that there is no high school in the vicinity. The nearest one is three hours away on foot. So going to school includes walking several miles on sand, crossing the river by boat and if the water level is low, then wading through the river (as in the adjacent photo). According to Prakash, if one were to remain dependent on that high school for education, then it was unlikely that one would learn anything much since the school closes down for four months every year due to the monsoon and the flood.

Most students who want to go to high school, are forced to move out of the village, but only very few of them can afford to do that. Also, this option is open only to boys. For the girls, moving is out of question, so a high school education only remains a distant dream.

With nearly no opportunities for education, the youth is resigned to working in the fields. Cultivation too holds no great promise as the fields get flooded or washed away every year and those that survive the flood are rendered unproductive by the sand deposits.

Prakash identifies education as the foremost need and demand of the youth of this region. This is closely followed by the need for generation of employment opportunities even as educational facilities are in the process of being scaled up.

Children at Rholi hanging out with no school to go to

Panchayat : Rholi;

Population : 1000, Anganwadi: 1;

School: Primary and Middle School; Children attending school: 300; Major Occupation: Labour

____________________________________________________

An interesting youth that the scouts met was twenty five year old Prakash Mani who is a resident of this flood-affected village which has a population of 1000. The entire district (Supaul) has only 52 high schools for a population of over five lakh (five hundred thousand) children aged between five and fourteen years. This means that for every ten thousand children passing out of middle school, assuming that they all reach middle school in the first place, there is only one high school. Prakash’s village is one of the exclusive few to have a middle school.

However, the quality of education at this middle school is quite poor, since there are no competent teachers. To top this of, is the fact that there is no high school in the vicinity. The nearest one is three hours away on foot. So going to school includes walking several miles on sand, crossing the river by boat and if the water level is low, then wading through the river (as in the adjacent photo). According to Prakash, if one were to remain dependent on that high school for education, then it was unlikely that one would learn anything much since the school closes down for four months every year due to the monsoon and the flood.

Most students who want to go to high school, are forced to move out of the village, but only very few of them can afford to do that. Also, this option is open only to boys. For the girls, moving is out of question, so a high school education only remains a distant dream.

With nearly no opportunities for education, the youth is resigned to working in the fields. Cultivation too holds no great promise as the fields get flooded or washed away every year and those that survive the flood are rendered unproductive by the sand deposits.

Prakash identifies education as the foremost need and demand of the youth of this region. This is closely followed by the need for generation of employment opportunities even as educational facilities are in the process of being scaled up.

Children at Rholi hanging out with no school to go to

Loukha

The second stop was Loukha village.

Panchayat : Loukha

Population : 600

Anganwadi: 1

School : Primary School

Children attending School : 100-150

Major Occupation: Cultivation

At Louka, the scouts met Lalan (photo alongside). Lalan is 9 years old and studies in the 4th grade at the primary school in the village. He belongs to the dalit caste and lives in the village with his mother, grand parents and two siblings. Four years ago Lalan lost his father to epileptic fits and ever since then, his mother Sita Devi has been responsible for his blind grandparents.

The family owns 7 bigha of agricultural land, which has been leased to five different people in the village to cultivate because there is no one in the family who can cultivate the land. Last year’s flood devastated 4 bigha of their agricultural land due to silt deposits and nothing can be cultivated on this any longer. This was their only hope to earn some money.

Lalan’s grandfather Masuharu has been suffering from tuberculosis for two years; and to treat this condition, his mother took a loan from a moneylender with a high interest rate. Unfortunately Masuharu’s condition is not improving and Lalan’s mother cannot repay the outstanding money and will not get a further loan anytime soon since their source of income (agriculture) had been destroyed this year. The current situation is so stark, that the family can afford to cook only once in a day. And due to this situation, Lalan misses school. He is anxious and does not know what he should do or how he can support his family.

Panchayat : Loukha

Population : 600

Anganwadi: 1

School : Primary School

Children attending School : 100-150

Major Occupation: Cultivation

At Louka, the scouts met Lalan (photo alongside). Lalan is 9 years old and studies in the 4th grade at the primary school in the village. He belongs to the dalit caste and lives in the village with his mother, grand parents and two siblings. Four years ago Lalan lost his father to epileptic fits and ever since then, his mother Sita Devi has been responsible for his blind grandparents.

The family owns 7 bigha of agricultural land, which has been leased to five different people in the village to cultivate because there is no one in the family who can cultivate the land. Last year’s flood devastated 4 bigha of their agricultural land due to silt deposits and nothing can be cultivated on this any longer. This was their only hope to earn some money.

Lalan’s grandfather Masuharu has been suffering from tuberculosis for two years; and to treat this condition, his mother took a loan from a moneylender with a high interest rate. Unfortunately Masuharu’s condition is not improving and Lalan’s mother cannot repay the outstanding money and will not get a further loan anytime soon since their source of income (agriculture) had been destroyed this year. The current situation is so stark, that the family can afford to cook only once in a day. And due to this situation, Lalan misses school. He is anxious and does not know what he should do or how he can support his family.

Chittauni

The first stop along the way was Chittauni.

Some basic facts about the village:

Panchayat: Chhitaun

Population: 400

Anganwadi: Not Present

School: Not Functional

Children attending school: 40

Major Occupation: Livestock

The scouts talking to youth in Chittauni to answer some questions

Kosi Barrage

The Voice of the Kosi

The River Voices Programme was set up by Praxis UK with the aim to raise awareness on the importance of rivers for tackling global poverty

As a start, there was a pilot expedition in April 2009, along the Kosi River in North India. As part of this expedition - The Voice of the Kosi, scouts went down this river to explore river related development issues and created their own youth manifesto.

They travelled down the river and stopped at nine villages along the way, to interact with other scout groups and young people to find out how they had been affected by floods and answers to these questions:

They collected all this information and then developed a youth manifesto which can be presented at different forums in India so that the issues of the youth along the river are resolved at the earliest.

One of the large scale projects that Praxis UK is involved with as part of River Voices is the Voice of the Nile. This is a partnership project between international organisations concerned about the sustainable development of rivers, and development organisations in the Nile basin. Its overall aim is the sustainable and equitable development of the Nile.

One of the large scale projects that Praxis UK is involved with as part of River Voices is the Voice of the Nile. This is a partnership project between international organisations concerned about the sustainable development of rivers, and development organisations in the Nile basin. Its overall aim is the sustainable and equitable development of the Nile.

- Particularly among young people…

- Of river related development issues

- Of global actions that need to be taken to address them

- Of personal actions you can take to protect them

As a start, there was a pilot expedition in April 2009, along the Kosi River in North India. As part of this expedition - The Voice of the Kosi, scouts went down this river to explore river related development issues and created their own youth manifesto.

The scouts on board the boat which took them along the Kosi river

- What do young people think is good about the river? How do young people depend upon the river?

- What’s best and worst about the river?

- What are all the different things the river gives you?

- What are the most important things the river gives you?

- What changes would young people like to see made to the river?

- What actions would youth like people to take?

They collected all this information and then developed a youth manifesto which can be presented at different forums in India so that the issues of the youth along the river are resolved at the earliest.

One of the large scale projects that Praxis UK is involved with as part of River Voices is the Voice of the Nile. This is a partnership project between international organisations concerned about the sustainable development of rivers, and development organisations in the Nile basin. Its overall aim is the sustainable and equitable development of the Nile.

One of the large scale projects that Praxis UK is involved with as part of River Voices is the Voice of the Nile. This is a partnership project between international organisations concerned about the sustainable development of rivers, and development organisations in the Nile basin. Its overall aim is the sustainable and equitable development of the Nile. It will do this through a process of building the capacity of the most vulnerable communities along the Nile to articulate their hopes and fears for the future, and so help inform local and regional policies regarding its future development. In 2010, an expedition made by representatives from each of the ten Nile basin countries, will highlight to the international community the common issues faced by the poorest people along the Nile, and many others rivers throughout the world.

The guiding principles of the project are defined by the motto: one river, one vision, one voice.

Click here read more about the River Voices project and its ongoing Voice of The Nile.What is the Kosi?

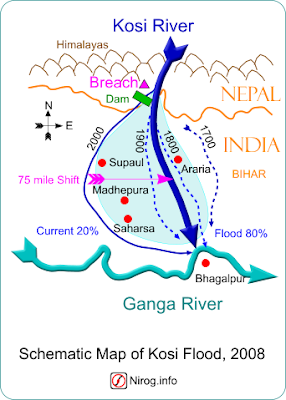

The Kosi, is a transboundary river between Nepal and India and is one of the tributaries of the Ganges that flows through the plains of the northern Indian state of Bihar. The Kosi is notorious for its devastating floods, which causes extreme damage to lives and livelihoods (flood related deaths in India account for a fifth of global flooding deaths).

The Kosi, is a transboundary river between Nepal and India and is one of the tributaries of the Ganges that flows through the plains of the northern Indian state of Bihar. The Kosi is notorious for its devastating floods, which causes extreme damage to lives and livelihoods (flood related deaths in India account for a fifth of global flooding deaths).Kosi embankments were built nearly five decades ago to confine the river and provide security from flooding. But despite this, breaches have occurred consistently and have left vast Kosi dependant regions in North Bihar, waterlogged. In 2008, the flood affected over 3 million people and the hardest hit were communities in 380 villages trapped between the two embankments of the river.

The Voice of the Kosi expedition was conceived to give marginalised groups along the Kosi river an active voice in their own equitable and sustainable development. The overall purpose was to contribute towards the sustainable and equitable development of river basins worldwide.

Geographical Background

The Kosi is a transboundary river between Nepal and India and is one of the tributaries of the Ganges that flows through the plains of the northern Indian state of Bihar.

The river, along with its tributaries, drains a total area of 69,300 km2 (26,800 sq mi) up to its confluence with the Ganges in India (29,400 km2/11,400 sq mi in China, 30,700 km2/11,900 sq mi in Nepal and 9,200 km2/3,600 sq mi in India). The watershed also includes part of Tibet, such as the Mount Everest region, and the eastern third of Nepal.

The Kosi river flows north to south, from Himalayas in Nepal & Tibet to Ganges in Bihar state of India. Usually due to heavy silt deposition, the river keeps taking longer curved paths to drain into the Ganges. Due to this, the river has shifted its course in the last 300 years. It is believed to have shifted its course over 120 kilometres (75 mi) from east to west.

Historical background of Kosi embankments

The Kosi has been part of folklore and legends in the basin area for several centuries. As explained in the above section, the river has historically been prone to floods. After India got its independence from the British in 1947, it drew up an agreement with Nepal to build the embankments in 1955. The idea behind this was to free millions of people from the devastation that was caused by the floods every year. According to the agreement, the responsibility of maintaining these embankments was vested in the Government of Bihar.

The embankments instead of protecting people ended up creating a bigger and much worse problem of trapping millions of people within it. This includes 386 villages spread across the four districts of Bihar (Saharsa, Supaul, Madhubani and Darbhanga) and 13 blocks (smaller administrative units – namely Basantpur, Kishanpur, Supaul, Nirmali (including Bhaptiahi), Nauhatta, Mahishi, Simri Bakhtiyarpur, Salkhua, Laukahi, Marauna, Ghoghardiha, Madhepur and Kiratpur)

The embankments instead of protecting people ended up creating a bigger and much worse problem of trapping millions of people within it. This includes 386 villages spread across the four districts of Bihar (Saharsa, Supaul, Madhubani and Darbhanga) and 13 blocks (smaller administrative units – namely Basantpur, Kishanpur, Supaul, Nirmali (including Bhaptiahi), Nauhatta, Mahishi, Simri Bakhtiyarpur, Salkhua, Laukahi, Marauna, Ghoghardiha, Madhepur and Kiratpur)Before the villagers understood the gravity of the situation and were able to raise the alarm and demand rehabilitation, it was already 1956 and 50kms of construction of the embankments had been completed. The Government for its part assured the ‘trapped’ people that the embankments, when completed, would cause only a marginal rise of four inches in the water level within them and that they had nothing to worry about. The people, however, maintained that the land around the Kosi sloped westwards and that any increase in the water level would spell doom for those trapped within the embankments.

At a meeting of the Kosi Control Board in Patna in 1956 members of the Central Water Commission opposed any move to resettle people displaced by construction of the embankments, on the plea that it would set a bad precedent and that people would begin demanding rehabilitation in all such projects. Good sense however prevailed and the rehabilitation issue remained alive. In 1956, the floods in the Kosi devastated those living within the embankments. Outside the embankments, the villages suffered water-logging from the stagnant water that could not make its way to the river because of the embankments.

A movement to rehabilitate villagers trapped within the Kosi embankments gained momentum in 1957. As resistance grew, the government prepared a rehabilitation package, but it later realised that it was severely under-budgeted and shelved the plan. As pressure mounted, the Government then announced a proportionate package of rehabilitation. The state announced in 1958, that the government would provide land to victims in flood-protected areas close to the embankments; that the government would arrange land for schools and roads; that rehabilitation sites would be provided with tanks, wells and tube wells for water supplied by the government; that house-building grants would be made available to the affected people; and that the government would ensure easy access to farmers’ fields by providing an adequate number of boats.

A movement to rehabilitate villagers trapped within the Kosi embankments gained momentum in 1957. As resistance grew, the government prepared a rehabilitation package, but it later realised that it was severely under-budgeted and shelved the plan. As pressure mounted, the Government then announced a proportionate package of rehabilitation. The state announced in 1958, that the government would provide land to victims in flood-protected areas close to the embankments; that the government would arrange land for schools and roads; that rehabilitation sites would be provided with tanks, wells and tube wells for water supplied by the government; that house-building grants would be made available to the affected people; and that the government would ensure easy access to farmers’ fields by providing an adequate number of boats.By 1960, only 70 villages were resettled. This meant that another nine years would be needed to ensure rehabilitation for all the embankment victims. By 1972-73, only 32,540 families out of a total of around 45,000 families were given their first grants to construct houses; 10,580 families were given second installments; none received the third and final installment. This arrangement did not work since the rehabilitation sites were slowly becoming waterlogged and people began to return to their old villages. The government interpreted this as a move by people to return to their ancestral property and so the rehabilitation process ended before it was even completed.

The state believed that not all the land within the Kosi embankments would be ruined as a result of the embankments, and that agriculture would continue to be practiced there. It was against this background that the government appointed a committee, in 1962, to look into the problems of agriculture, health, industry, revenue collection, extension of securities and cooperation. The state development commissioner, land reforms commissioner and chief administrator of the Kosi project were all members of this committee. But the committee did not perform.

Then, in 1967, another committee was constituted under the chairmanship of the Kosi area development commissioner whose job it was to suggest programmes for victims of the project, in the agriculture, cooperation, industrial development and economic rehabilitation sectors. This committee too was non-functional. In 1981, another committee was constituted to look into the problem of economic rehabilitation of the embankment victims. This committee gave its report in 1982; in 1987 the government accepted its recommendations.

Then, in 1967, another committee was constituted under the chairmanship of the Kosi area development commissioner whose job it was to suggest programmes for victims of the project, in the agriculture, cooperation, industrial development and economic rehabilitation sectors. This committee too was non-functional. In 1981, another committee was constituted to look into the problem of economic rehabilitation of the embankment victims. This committee gave its report in 1982; in 1987 the government accepted its recommendations.Based on the recommendations of this Committee, the state government constituted the Kosi Pirit Vikas Pradhikar (Kosi Sufferers Development Authority) the same year. While recommending the constitution of the Authority, the then chief minister of Bihar, asserted that there was probably no other place in the country where so many people were exposed to the fury of river flooding. The people had lost all hope of a better life, and his “determined government” was committed to their overall development.

However, since its inception in 1987, the Kosi Sufferers Development Authority has remained a defunct body. It has no building or office of its own; it has no vehicles; and ‘deputation employees’ man it. It does not even have a budget.

The situation today

Education

There are few primary schools within the embankments and the schools which do exist are of very low infrastructural quality (eg: school buildings do not have roofs.) As a result very few students and teachers are enrolled here

Health

Doctors and health department personnel generally do not visit the health centres in the area and during the rainy season, they cannot do so even if they wanted to because of the river’s heavy currents and cutting off of all means of access to these villages

Infrastructure

There is no electricity, no permanent roads, no colleges, no hospitals, no cinemas, no banks and no government offices in the embankment villages.

Employment

Even though there is a provision for reservation of 15% of jobs in the districts for the victims of the Kosi embankments, so far, no one has benefited from this scheme – not even for positions in the Kosi Sufferers Development Authority.

Social stigma

The people living within the embankments avoid marriages as there are no employment opportunities and therefore is no scope to feed families. The communities are slowly being forgotten since even the politicians do not pursue their issues at the appropriate forums.

A typical house, a typical school and a typical village.....

WITHIN THE KOSI EMBANKMENTS

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)